Around Our Town Ep. 44 – Famine Evictions in Tipperary

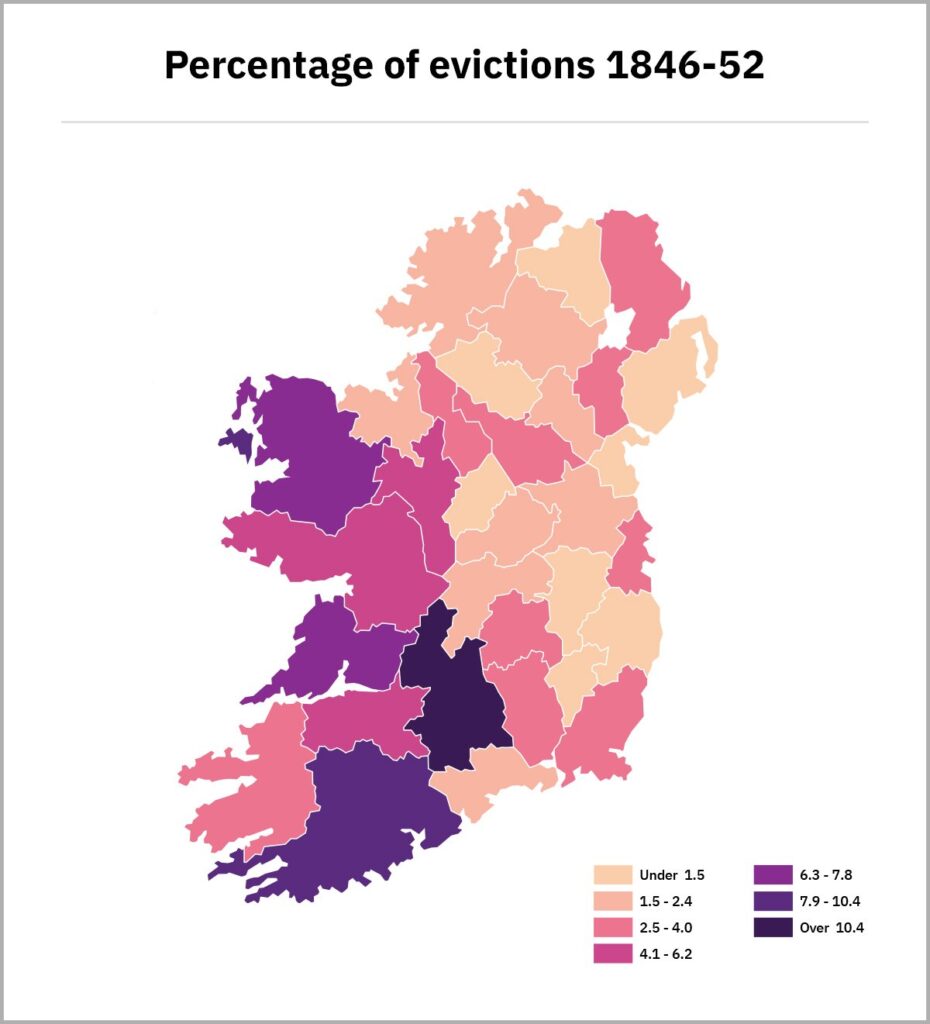

One of the most emotive aspect of the Great Irish Famine is eviction. The image of an emaciated family hopelessly standing aside as their cottage is demolished endures to this today. Dr Ciarán Reilly of Maynooth University estimates that over 250,000 people were made homeless as a result of eviction during the famine years. Some estimates put the figure at closer to half million. Tipperary was particularly hard hit. By 1847 Tipperary had the highest percentage of evictions in the country. The rate in Tipperary was 10 times that in Fermanagh, the county least effected.

While eviction had always been a feature of the early famine years 1847 saw a dramatic acceleration in the number of cases coming before the courts. This was ostensible as a result of the introduction in that year of an amendment to the Poor Law Act. This amendment marked a change in the British Government’s approach to famine relief in Ireland. The Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, sought to shift the financial burden from the exchequer to the Irish landowners themselves. Two provisions in particular contained within the amendment would have a devastating impact.

Landlords were now responsible for the payment of rates on land or property leased with a rental value of less than four pounds annually. To those landlords who had allowed their estates to be extensively subdivided the financial implications were obvious. Many landlords embarked on large scale campaign of clearances in order to limit their tax liability. Nominally tenants would be evicted for the non payment of rent. But this was simply a pretext to allow landlords to eliminate smaller holdings.

The 1847 amendment also redefined the criteria by which the destitute could access relief. The notorious ‘Gregory Clause’ precluded those on holdings greater than a quarter on an acre accessing famine relief of any kind. This legislation was framed in the belief that only the truly desperate should qualify for relief. This had a devastating effect on an already starving populous. It precipitated a flood of voluntary surrenders as people abandoned their homes in the hopes of gaining a place in a workhouse.

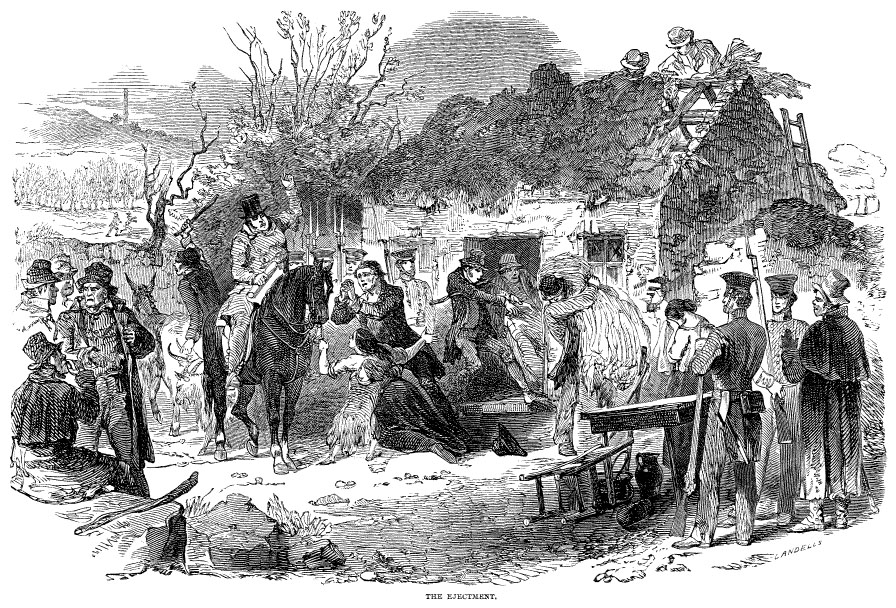

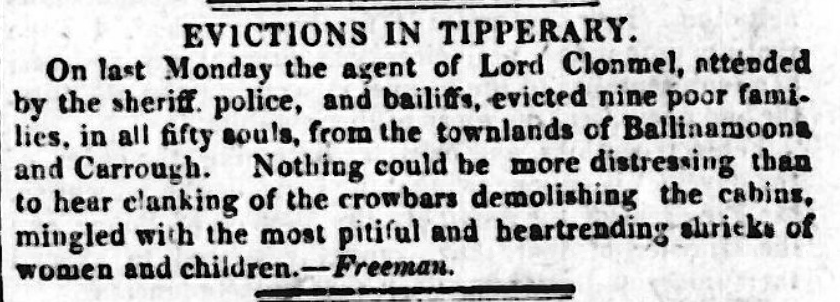

An article from the Tipperary Vindicator dated the 2nd of December 1848 describes the clearance system as a progress of extermination. No community was left untouched. The evictions themselves followed a similar pattern. Following a court decision, an official such as a bailiff accompanied by an agent of the landlord would move in to take possession. While police and military had no formal role in evictions they were empowered to attend where it was thought resistance maybe offered or unrest break out. The tenant’s cottage would be rendered uninhabitable in short order by a team of ‘crowbar men’.

One of the most infamous mass eviction which took place in Tipperary occurred in Toomevara in May 1849. Here, the landlord, Rev. Massey Dawson evicted 500 tenants from his property in and around the village. The Tipperary Vindicator of the 26th of May reported on a scene of utter devastation and human suffering. The correspondent describes a posse of ten or twelve men armed with crowbars and supported by 40 or so police descending upon the village. He details a chaotic atmosphere as families are led out of their homes into the rain with what little effects they possess. The frantic shrieking and crying of the tenants can be heard as the roofs and walls of their dwellings are tumbled down. A report from the same newspaper dated a week later describes scenes reminiscent of a modern day refugee camp. Hundreds of the destitute had erected rudimentary shelters in ditches and along roadsides on the outskirts of the village. Father Meagher the Parish Priest counted 116 such huts on Fethard Street alone.