The Tipperary Banking Collapse of 1856

On Sunday morning the 17th of February 1856 the body of man was discovered on Hamstead Heath in London. The body was that John Sadleir Esq. MP, a native of Shronell, Co. Tipperary. It would later be confirmed that Sadleir had committed suicide by drinking a phial of prussic acid. He had been one of the founding members of the Tipperary Joint Stock Bank. The bank was about to collapse as a result of huge sums of money Sadleir had misappropriated to fund a series of failed speculations in commodities and railway shares. A study of Sadleir’s frauds estimated the figures involved to be in excess of £1,000,000. The banks collapse resulted in financial ruination for shareholders, creditors and depositors alike. However, in Tipperary the losses suffered by depositors in particular was keenly felt. They were for the most part farmers and shopkeepers.

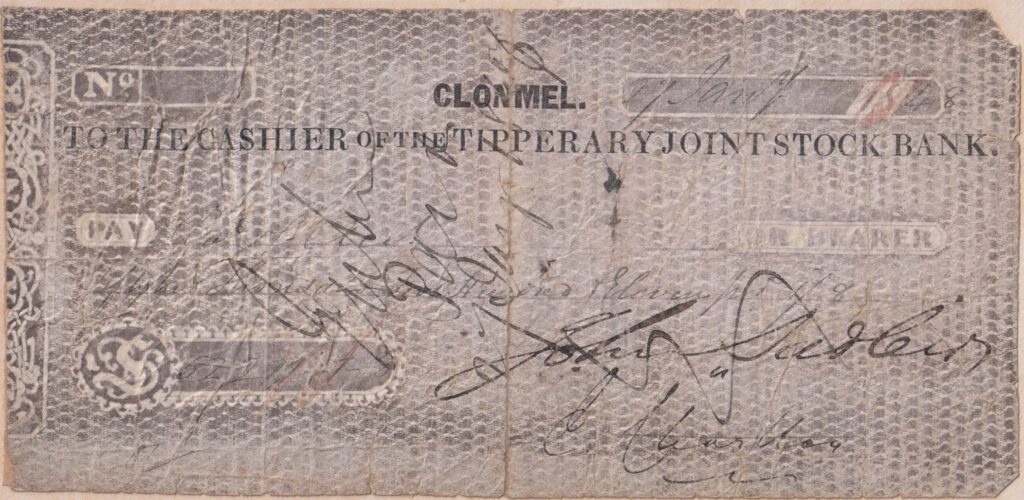

John Sadleir was born in 1813 at Shronell House near Tipperary Town to a wealthy and politically influential Catholic family. He was educated at Clongowes Wood College and subsequently joined his uncles legal practice in Dublin. His early life is a marked by a string successful ventures both professional and political. The Sadleirs had banking in their blood. Their grandfather, James Scully had founded a small private bank. This would in 1838 form the foundation of Sadleir’s own bank, the Tipperary Joint Stock Bank. The bank was an astonishing success and by 1845 it had a head office on Duncan Street (now Sarsfield Street) in Clonmel as well branches in Tipperary Town, Nenagh, Thurles, Carrick-on-Suir, Thomastown, Roscrea, Athy and Carlow.

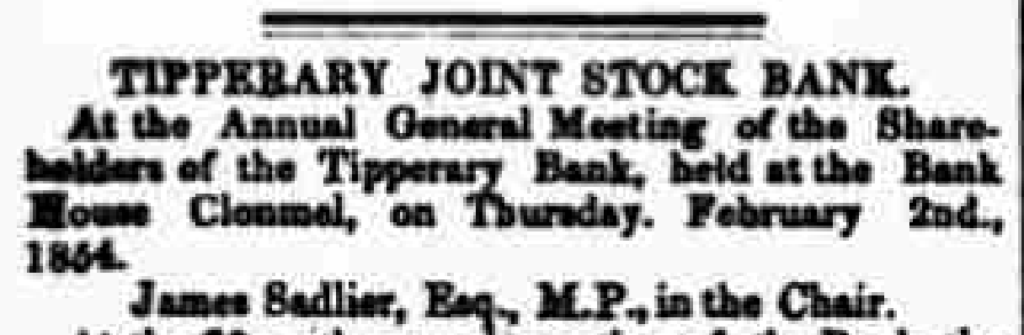

By 1846 John Sadleir quit his uncles legal practice and focused his full attention on the world of high finance and politics. The following year he was elected MP for Carlow. Robert Keating a cousin of the Sadleir’s was elected MP for Waterford that same year. John’s brother James and another cousin, Francis Scully would later follow them into the House of Commons as MPs for Tipperary. Together they formed a Catholic faction which sought to promote the rights of small landowners. At this point James Sadleir had become managing director and chairman of the bank. John Sadleir moved to London seeking to capitalise on the success of the Tipperary Bank. He expanded his business interests and amassed a vast fortune financing railway projects across Europe. He also bought up the estates of Irish families that had been bankrupted following the famine.

It would seem that the Sadleirs could do no wrong. However from about 1853 this began to change. In that year John Sadleir was offered and accepted the position of junior lord of the treasury in the government of the day. His Carlow electors were outraged viewing his actions as a betrayal and later in1853 he was oust from his seat. His disgrace was complete in 1854 when it came to light that he had attempted to pressurise and imprison an elector who refused to vote for him. This corrupt behaviour would turn out to be but the tip of the iceberg.

The Sadleir’s bank was in fact insolvent. Over many years John Sadleir had, with the full knowledge of his brother, bled the bank dry. Through various fraudulent means John Sadleir had funded a scheme of wild and unsuccessful speculations in hemp, sugar and iron. As the loss mounted he had become desperate. He held a £288,000 overdraft with the bank and at one point sold a cousin of his £20,000 worth of forged railway company shares. At the beginning of 1856 rumours began to circulate in London that the Tipperary bank was in trouble. John Sadleir was scrambling to secure capital to prop up the bank. By February 1856 he was out road. The bank’s London clearing house refused to process transactions. With nowhere left to turn John Sadleir took his own life near a tavern in north London. His brother James disappeared. He would later turn in Paris before eventually settling in Zurich. He would never answer in a court of law for the immense hardship he and his brother’s actions thrust upon so many.

James O’Shea (Tipperary Joint Stock Bank 1838-1856) paints a bleak picture of what happened in the aftermath of the bank’s collapse. When news of the bank’s failure reached Tipperary panic broke out. Branches up and down the county were flooded with angry depositors. They broke down doors to gain entry and in one case the floor of the bank was dug up in a vain attempt to recover lost savings. The police were called to maintain order outside the bank headquarters in Clonmel. In the weeks and months that followed, newspapers reported tragic stories of people who had suffered greatly when the bank collapsed. One woman lost her life savings of £100. She had wanted to send her stepson to America. The parish priest in Thomastown lost the parish savings intended to put a new roof on the church. In one horrific case a farmer had beaten his wife death after their savings of £300 had not been withdrawn in time.

Historian Michael Ahern in his book Threads in a Clonmel Tapestry claims that John Sadleir’s wild speculations stemmed from a need to offset huge gambling losses he suffered in gentlemen’s clubs in London. Rev William Burke in his History of Clonmel takes a less sympathetic view asserting that the bank was, from the beginning, an elaborate rouse by the Sadleirs to get their hands on depositors’ money. For the ordinary decent folk of Tipperary, who fell foul of the ill-fated Tipperary Joint Stock Bank, the result was all the same.